Surface states

Surface states are electronic states found at the surface of materials. They are formed due to the sharp transition from solid material that ends with a surface and are found only at the atom layers closest to the surface. The termination of a material with a surface leads to a change of the electronic band structure from the bulk material to the vacuum. In the weakened potential at the surface, new electronic states can be formed, so called surface states.

Contents |

Origin of surface states at condensed matter interfaces

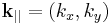

As stated by Bloch's theorem, eigenstates of the single-electron Schrödinger equation with a perfectly periodic potential, a crystal, are Bloch waves [1]

Here  is a function with the same periodicity as the crystal, n is the band index and k is the wave number. The allowed wave numbers for a given potential are found by applying the usual Born–von Karman cyclic boundary conditions [1]. The termination of a crystal, i.e. the formation of a surface, obviously causes deviation from perfect periodicity. Consequently, if the cyclic boundary conditions are abandoned in the direction normal to the surface the behavior of electrons will deviate from the behavior in the bulk and some modifications of the electronic structure has to be expected.

is a function with the same periodicity as the crystal, n is the band index and k is the wave number. The allowed wave numbers for a given potential are found by applying the usual Born–von Karman cyclic boundary conditions [1]. The termination of a crystal, i.e. the formation of a surface, obviously causes deviation from perfect periodicity. Consequently, if the cyclic boundary conditions are abandoned in the direction normal to the surface the behavior of electrons will deviate from the behavior in the bulk and some modifications of the electronic structure has to be expected.

A simplified model of the crystal potential in one dimension can be sketched as shown in figure 1 [2]. In the crystal, the potential has the periodicity, a, of the lattice while close to the surface it has to somehow attain the value of the vacuum level. The step potential (solid line) shown in figure 1 is an oversimplification which is mostly convenient for simple model calculations. At a real surface the potential is influenced by image charges and the formation of surface dipoles and it rather looks as indicated by the dashed line.

Given the potential in figure 1, it can be shown that the one-dimensional single-electron Schrödinger equation gives two qualitatively different types of solutions.[3].

- The first type of states (see figure 2) extends into the crystal and has Bloch character there. These type of solutions correspond to bulk states which terminate in an exponentially decaying tail reaching into the vacuum.

- The second type of states (see figure 3) decays exponentially both into the vacuum and the bulk crystal. These type of solutions correspond to states, with wave functions localized close to the crystal surface.

The first type of solution can be obtained for both metals and semiconductors. In semiconductors though, the associated eigenenergies have to belong to one of the allowed energy bands. The second type of solution exists in forbidden energy gap of semiconductors as well as in local gaps of the projected band structure of metals. It can be shown that the energies of these states all lie within the band gap. As a consequence, in the crystal these states are characterized by an imaginary wavenumber leading to an exponential decay into the bulk.

Shockley states and Tamm states

In the discussion of surface states, one generally distinguishes between Shockley states[4] and Tamm states[5]. However there is no real physical distinction between the two terms, only the mathematical approach in describing surface states is different.

- Historically, surface states that arise as solutions to the Schrödinger equation in the framework of the nearly-free electron approximation for clean and ideal surfaces, are called Shockley states. Shockley states are thus states that arise due to the change in the electron potential associated solely with the crystal termination. This approach is suited to describe normal metals and some narrow gap semiconductors. Figures 1 and 2 are examples of Shockley states, derived using the nearly free electron approximation.

- Surface states that are calculated in the framework of a tight-binding model are often called Tamm states. In the tight binding approach, the electronic wave functions are usually expressed as linear combinations of atomic orbitals (LCAO). In contrast to the nearly free electron model used to describe the Shockley states, the Tamm states are suitable to describe also transition metals and wide gap semiconductors[2].

Shockley states

Surface states in metals

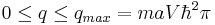

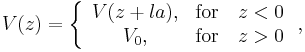

A simple model for the derivation of the basic properties of states at a metal surface is a semi-infinite periodic chain of identical atoms.[6] In this model, the termination of the chain represents the surface, where the potential attains the value V0 of the vacuum in the form of a step function, figure 1. Within the crystal the potential is assumed periodic with the periodicity a of the lattice. The Shockley states are then found as solutions to the one-dimensional single electron Schrödinger equation

with the periodic potential

where l is an integer. The solution must be obtained independently for the two domains z<0 and z>0, where at the domain boundary (z=0) the usual conditions on continuity of the wave function and its derivatives is applied. Since the potential is periodic deep inside the crystal the electronic wave functions must be Bloch waves here. The solution in the crystal is then a linear combination of an incoming and a wave reflected from the surface. For z>0 the solution will be required to decrease exponentially into the vacuum

The wave function for a state at a metal surface is qualitatively shown in figure 2. It is an extended Bloch wave within the crystal with an exponentially decaying tail outside the surface. The consequence of the tail is a deficiency of negative charge density just inside the crystal and an increased negative charge density just outside the surface, leading to the formation of a dipole double layer. The dipole perturbs the potential at the surface leading, for example, to a change of the metal work function.

Surface states in semiconductors

The nearly free electron approximation can be used to derive the basic properties of surface states for narrow gap semiconductors. The semi-infinite linear chain model is also useful in this case[3]. However, now the potential along the atomic chain is assumed to vary as a cosine function

![\begin{alignat}{2}

V(z)&= V\left[\exp\left(i\frac{2\pi z}{a}\right)%2B\exp\left(-i\frac{2\pi z}{a}\right)\right] \\

&=2 V\cos\left(\frac{2\pi z}{a}\right), \\

\end{alignat}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/a2efdf2f0a19c9740bb3dbbde547eb59.png)

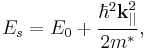

whereas at the surface the potential is modeled as a step function of height V0. The solutions to the Schrödinger equation must be obtained separately for the two domains z < 0 and z > 0. In the sense of the nearly free electron approximation, the solutions obtained for z < 0 will have plane wave character for wave vectors away from the Brillouin zone boundary  , where the dispersion relation will be parabolic, as shown in figure 4. At the Brillouin zone boundaries, Bragg reflection occurs resulting in a standing wave consisting of a wave with wave vector

, where the dispersion relation will be parabolic, as shown in figure 4. At the Brillouin zone boundaries, Bragg reflection occurs resulting in a standing wave consisting of a wave with wave vector  and wave vector

and wave vector  .

.

Here  is a lattice vector of the reciprocal lattice (see figure 4). Since the solutions of interest are close to the Brillouin zone boundary, we set

is a lattice vector of the reciprocal lattice (see figure 4). Since the solutions of interest are close to the Brillouin zone boundary, we set  , where κ is a small quantity. The arbitrary constants A,B are found by substitution into the Schrödinger equation. This leads to the following eigenvalues

, where κ is a small quantity. The arbitrary constants A,B are found by substitution into the Schrödinger equation. This leads to the following eigenvalues

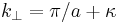

demonstrating the band splitting at the edges of the Brillouin zone, where the width of the forbidden gap is given by 2V. The electronic wave functions deep inside the crystal, attributed to the different bands are given by

Where C is a normalization constant. Near the surface at z = 0, the bulk solution has to be fitted to an exponentially decaying solution, which is compatible with the constant potential V0.

It can be shown that the matching conditions can be fulfilled for every possible energy eigenvalue which lies in the allowed band. As in the case for metals, this type of solution represents standing Bloch waves extending into the crystal which spill over into the vacuum at the surface. A qualitative plot of the wave function is shown in figure 2.

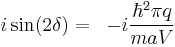

If imaginary values of κ are considered, i.e. κ = - i·q for z ≤ 0 and one defines

one obtains solutions with a decaying amplitude into the crystal

The energy eigenvalues are given by

E is real for large negative z, as required. Also in the range  all energies of the surface states fall into the forbidden gap. The complete solution is again found by matching the bulk solution to the exponentially decaying vacuum solution. The result is a state localized at the surface decaying both into the crystal and the vacuum. A qualitative plot is shown in figure 3.

all energies of the surface states fall into the forbidden gap. The complete solution is again found by matching the bulk solution to the exponentially decaying vacuum solution. The result is a state localized at the surface decaying both into the crystal and the vacuum. A qualitative plot is shown in figure 3.

Surface states of a three-dimensional crystal

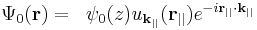

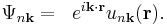

The results for surface states of a monoatomic linear chain can readily be generalized to the case of a three-dimensional crystal. Because of the two-dimensional periodicity of the surface lattice Bloch's theorem must hold for translations parallel to the surface. As a result, the surface states can be written as the product of a Bloch waves with k-values  parallel to the surface and a function representing a one-dimensional surface state

parallel to the surface and a function representing a one-dimensional surface state

The energy of this state is increased by a term  so that we have

so that we have

where m* is the effective mass of the electron. The matching conditions at the crystal surface, i.e. at z=0, have to be satisfied for each  separately and for each

separately and for each  a single, but generally different energy level for the surface state is obtained.

a single, but generally different energy level for the surface state is obtained.

True surface states and surface resonances

A surface state is described by the energy  and its wave vector

and its wave vector  parallel to the surface, while a bulk state is characterized by both

parallel to the surface, while a bulk state is characterized by both  and

and  wave numbers. In the two-dimensional Brillouin zone of the surface, for each value of

wave numbers. In the two-dimensional Brillouin zone of the surface, for each value of  therefore a rod of

therefore a rod of  is extending into the three-dimensional Brillouin zone of the Bulk. Bulk energy bands that are being cut by these rods allow states that penetrate deep into the crystal. One therefore generally distinguishes between true surface states and surface resonances. True surface states are characterized by energy bands that are not degenerate with bulk energy bands. These state are existing in the forbidden energy gap only and are therefore localized at the surface, similar to the picture given in 'figure 3. At energies where a surface and bulk state are degenerate surface and the bulk state can mix, forming a surface resonance. Such state can propagate deep into the bulk similar to Bloch waves, while retaining an enhanced amplitude close to the surface.

is extending into the three-dimensional Brillouin zone of the Bulk. Bulk energy bands that are being cut by these rods allow states that penetrate deep into the crystal. One therefore generally distinguishes between true surface states and surface resonances. True surface states are characterized by energy bands that are not degenerate with bulk energy bands. These state are existing in the forbidden energy gap only and are therefore localized at the surface, similar to the picture given in 'figure 3. At energies where a surface and bulk state are degenerate surface and the bulk state can mix, forming a surface resonance. Such state can propagate deep into the bulk similar to Bloch waves, while retaining an enhanced amplitude close to the surface.

Tamm states

Surface states that are calculated in the framework of a tight-binding model are often called Tamm states. In the tight binding approach, the electronic wave functions are usually expressed as a linear combinations of atomic orbitals (LCAO), see figure 5. In this picture, it is easy to comprehend that the existence of a surface will give rise to surface states with energies different from the energies of the bulk states: Since the atoms residing in the topmost surface layer are missing their bonding partners on one side their orbitals have less overlap with the orbitals of neighboring atoms. The splitting and shifting of energy levels of the atoms forming the crystal is therefore smaller at the surface than in the bulk.

If a particular orbital is responsible for the chemical bonding, e.g. the sp3 hybrid in Si or Ge, it is strongly affected by the presence of the surface, bonds are broken, and the remaining lobes of the orbital stick out from the surface. They are called dangling bonds. The energy levels of such states are expected to significantly shift from the bulk values.

In contrast to the nearly free electron model used to describe the Shockley states, the Tamm states are suitable to describe also transition metals and wide bandgap semiconductors.

Extrinsic surface states

Surface states originating from clean and well ordered surfaces are usually called intrinsic. These states include states originating from reconstructed surfaces, where the two-dimensional translational symmetry gives rise to the band structure in the k space of the surface.

Extrinsic surface states are usually defined as states not originating from a clean and well ordered surface. Surfaces that are fit into the category extrinsic are [7]:

- Surfaces with defects, where the translational symmetry of the surface is broken.

- Surfaces with adsorbates

- Interfaces between two material such as a semiconductor-oxide or semiconductor-metal interfaces

- Interfaces between solid and liquid phases.

Generally for extrinsic surface states is that they cannot easily be characterized in terms of their chemical, physical or structural properties.

Angle resolved photoemission spectroscopy (ARPES)

An experimental technique to measure the dispersion of surface states is angle resolved photoemission spectroscopy (ARPES) or angle resolved ultraviolet photoelectron spectroscopy (ARUPS).

References

- ^ a b C. Kittel (1996). Introduction to Solid State Physics. Wiley. pp. 80–150. ISBN 0471142867.

- ^ a b K. Oura, V.G. Lifshifts, A.A. Saranin, A. V. Zotov, M. Katayama (2003). "11". Surface Science. Springer-Verlag, Berlin Heidelberg New York.

- ^ a b Feng Duan, Jin Guojin (2005). "7". Condensed Matter Physics:Volume 1. World Scientific. ISBN 981256070X.

- ^ W. Shockley (1939). "On the Surface States Associated with a Periodic Potential". Phys. Rev. 56 (4): 317. Bibcode 1939PhRv...56..317S. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.56.317.

- ^ I. Tamm (1932). Phys. Z. Soviet Union 1: 733.

- ^ Sydney G. Davison, Maria Steslicka (1996). "3-5". Basic Theory of surface states. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Frederick Seitz, Henry Ehrenreich, David Turnbull (1996). Solid State Physics. Academic Press. pp. 80–150. ISBN 0126077290.

![\begin{align}

\left[-\frac{\hbar^2}{2m}\frac{d^2}{dz^2}%2BV(z)\right]\Psi(z) &=& E\Psi(z),

\end{align}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/d12505ede328ae490badae09e6a39771.png)

![\begin{align}

\Psi(z) &=& \left\{

\begin{array}{cc}

Bu_{-k}e^{-ikz}%2BCu_{k}e^{ikz},&\textrm{for} \quad z<0\\

A\exp\left[-\sqrt{2m(V_0-E)}\frac{z}{\hbar}\right],& \textrm{for}\quad z>0

\end{array}\right.,

\end{align}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/f5bcb0fc6eae8ff5deda8679c6e4267e.png)

![\begin{align}

\Psi(z) &=& Ae^{ik z}%2B Be^{i[k -(2\pi/a) ]z}.

\end{align}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/5a4090888dcd2fe6740ed525c167cd59.png)

![\begin{align}

E &=& \frac{\hbar^2}{2m}\left(\frac{\pi}{a}%2B\kappa\right)^2\pm |V|\left[-\frac{\hbar^2 \pi \kappa}{m a |V|}\pm \sqrt{\left(\frac{\hbar^2 \pi \kappa}{ma |V|}\right)^2%2B1}\right]

\end{align}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/0ceaad0ee4fee4ff4833d1d63d56a447.png)

![\begin{align}

\Psi_i &=& Ce^{i\kappa z} \left(

e^{i\pi z/a} %2B \left[-\frac{\hbar^2 \pi \kappa}{m a |V|}\pm \sqrt{\left(\frac{\hbar^2 \pi \kappa}{ma |V|}\right)^2%2B1}\right]e^{-i\pi z/a}\right)

\end{align}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/ca01916aad80b184e3c300964d64ad70.png)

![\begin{align}

\Psi_0 &=& D\exp\left[-\sqrt{\frac{2m}{\hbar^2}(V_0-E)z}\right]

\end{align}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/1a7e110ebf8501d944213c60fc4238b6.png)

![\begin{align}

\Psi_i(z\leq0) &=& Fe^{qz}\left[\exp\left[i\left(\frac{\pi}{a}z\pm\delta\right)\right]\pm\exp\left[-i\left(\frac{\pi}{a}z\pm\delta\right)\right]\right]e^{\mp i\delta}

\end{align}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/2ea6f52af225eea5dddeeb90278af451.png)

![\begin{align}

E &=& \frac{\hbar^2}{2m}\left[\left(\frac{\pi}{a}\right)^2-q^2\right]\pm V\sqrt{1-\left(\frac{\hbar^2\pi q}{maV}\right)^2}

\end{align}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/0057fe656c28f7606a393e9c62060340.png)